Last week, the ongoing legal battle between Process & Industrial Developments (P&ID) and the Federal Government of Nigeria came to a head when the English Commercial Court granted permission for the enforcement of P&ID’s arbitration award against Nigeria in the UK.

That judgment sent shock waves around the country. The award – over $9 billion, and counting – is one of the largest arbitration awards ever granted.

Previously, BWN set out to investigate the founders of P&ID – Michael Quinn and Brendan Cahill. As we found out in that report, Cahill and Quinn had, prior to setting up P&ID, garnered over 30 years experience doing business in Nigeria, and had handled several high profile projects in the country.

As part of our story, we highlighted one of their largest government contracts in Nigeria that took place in the 1990s, commonly referred to as ‘The Butanisation Project.’

In recent weeks, BWN has sought to investigate this project in more detail.

In the early 1990s there was a serious energy crisis facing the North where only 4 per cent of rural communities had access to electricity. Burning wood as a source of fuel for cooking and light was commonplace. This led to serious consequences, and according to the World Health Organization (WHO) at the time, “Over 98,000 Nigerian women died [sic] annually from use of firewood. If a woman cooks breakfast, lunch and dinner, it is equivalent to smoking between three and 20 packets of cigarettes a day.”

This was also causing an environmental crisis. The rate of exploitation of trees for fuel was increasing significantly, with the annual rate of deforestation averaging 3.5 percent between 1980 and 1990. Clearly, something had to be done to address these twin health and environmental crises.

To address the lack of reliable access to electricity, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) sought to leverage the country’s abundant supplies of natural gas. However, there was a big problem: Nigeria lacked an adequate gas distribution infrastructure and, building out natural gas pipelines, especially in the North, was not economically viable.

NNPC had another idea: leverage cheap and abundant butane gas, a byproduct of natural gas, and build a network of butanisation storage and distribution depots across the North.

Butane was a logical solution as it is cheaper and more efficient with a lower emissions profile compared to coal and burning wood.

The NNPC plan consisted of two components: 9 storage and distribution depots, a contract for the construction of the depots and the importation of 48-1,000 tonne high pressure storage vessels.

BWN has found that the P&ID founders, Mr Cahill and Mr Quinn, through their company at the time, MF Kent, were awarded a contract to build 6 out of the 9 distribution depots of butane.

The NNPC issued a tender for the manufacturing of these high-pressure storage vessels. A number of companies expressed interest in the project, but according to BWN’s sources involved in the process, none of them were in Nigeria, or even African. All of these companies intended to undertake the construction of the vessels inside their home countries and then export them to Nigeria. At the time, it was thought impossible for a Nigerian company to be able to build vessels like these.

However, Quinn and Cahill’s proposal was different. They saw a unique opportunity to create an entirely new industry for Nigeria. The idea was twofold: first, identify a new manufacturing facility in Nigeria, and second, persuade a first-rate Western manufacturer to develop a technology transfer partnership that would enable Nigeria to build the high pressure vessels inside the country.

But could this work?

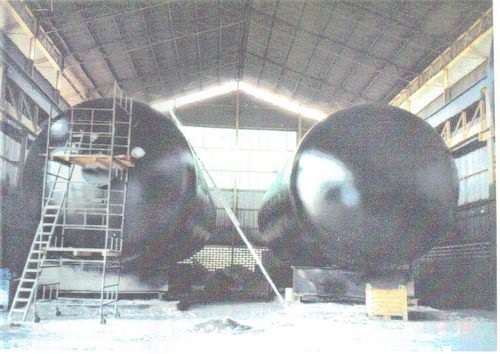

Manufacturing high-pressure tanks represented a major engineering and logistical challenge for Nigeria. Never before had such tanks been manufactured in Nigeria. Moreover, at the time, there were only a handful of companies worldwide that had the capacity and expertise to construct these types of vessels. The vessels are extremely intricate and complicated to manufacture, requiring specialized welding and fabrication due to their sheer size. The welding is especially critical as the tiniest leak could result in a catastrophic explosion.

And they needed a partner with the know-how to train Nigerian workers. The entrepreneurial Irishmen proposed their concept to the highly regarded manufacturer of pressure vessels in England, FKI Babcock Robey Limited.

Babcock Robey was nervous, understandably. Never before had they attempted such an undertaking. One of their biggest concerns was establishing a payment system that satisfied all parties: they would not move ahead until this was resolved.

Quinn and Cahill had a solution. They established a milestone payment structure where the Nigerian government would pay as the project progressed, rather than at the end of the project. It was a structure that unblocked the logjam and allowed the investment and training to move ahead. This protected Babcock Robey against their concerns that they could be in a cash-negative situation. And in exchange for their services, BWN has established that Babcock Robey paid Quinn and Cahill a commission for their services, on a pro rata basis throughout the contract.

With a partnership in place, Quinn and Cahill sought out a facility to build the vessels. By a stroke of Irish luck, they found an underutilized engineering and fabrication plant in Ekeke, Lagos, that was owned by Dorman Long. While the facility was in good condition, it was not being operated to its fullest potential. Quinn and Cahill approached Dorman Long, proposing to use the facility for the construction of the high pressure vessels.

Their role in this project – as entrepreneurs and facilitators – is quite typical of what BWN found in our previous investigation looking into many of Cahill & Quinn’s activities in Nigeria over the years.

Some in the West have questioned whether Dorman Long is real or fake – even nicknamed the company “Dormalog” or “Domalong”. We shared this concern. However, BWN’s investigation has established that this company is 100% Nigerian owned and has been a vocal player in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. Dorman Long now operates three manufacturing sites in the Lagos area; Idi-Oro, Naval Dockyard and Agege.

With an agreement in place with Babcock Robey and Dorman Long, Quinn and Cahill pitched the concept to the NNPC, suggesting a contract be structured around a milestone basis, setting a timeline of goals to ensure the project remained on schedule. Milestone payments would keep the manufacturer cash positive to compensate for the high risk involved in setting up the operation in Nigeria.

The attraction of creating a home-made industry was key to the project securing support from the Nigerian authorities. With the green light, manufacturing of the vessels got underway, and M.F. Kent began work on their six depots. Inside Dorman Long, the Babcock Robey team trained Nigerian manufacturers, successfully completing all of the high pressure vessels. As a direct result of that technology transfer, Quinn and Cahill helped create a new generation of indigenous manufacturers in Nigeria to service the country’s rapidly growing oil and gas industry.

Since that time, Dorman Long has transformed into a power house for fabrication. The successful construction of the Butanisation depots accentuated the need to build greater capacity for fabricating even more complex equipment. Dorman Long rose to the challenge. The company now operates three manufacturing facilities, supplying a broad range of heavy engineering products and services, which hitherto could only be obtained by importing them into Nigeria.

There are those who claim that the Butanisation project was fiction and never happened. BWN’s investigation has uncovered the reality: a legacy of jobs and investment. The legacy of this project is ubiquitous: new jobs, and a new industry worth hundreds of millions to the Nigeria economy. It was indeed a shared success story – the Nigerian authorities involved, as well as Babcock Robey and local engineers, all played their part. It was a remarkable example of what can be achieved by fusing good decisions by government with efficient private sector investment and expertise.

The Butanisation project was one of the highlights of a 30-year long business career inside Nigeria for Quinn and Cahill during which they made deals in everything from medicine kits, to tanks, to ports. They started with the Butanisation project as a dream of “what could be.”

Whatever concerns have been expressed in some quarters that Cahill and Quinn were Johnny-come-latelys with P&ID, the Butanisation project proves that this narrative is not accurate.

We all know by now that the P&ID gas project did not have the same happy ending – the Nigerian government’s inability to uphold their end of the agreement, resulted in an arbitration tribunal finding the government liable for an arbitration award of over $9 billion, with the U.K. court now giving the green light to seize Nigerian assets.

It could have been turned out so differently.