Naira devaluation is often presented as a necessary economic adjustment, but for a country with Nigeria’s distorted structure, it ends up transferring wealth to the government while impoverishing the people and squeezing the private sector.

It is easier to discuss naira devaluation in a country with a wide gap between the rich and the poor than to attempt currency redenomination. Meanwhile, the lowest naira denominations have become practically useless, erased by inflation without an official announcement ending their legal tender status, yet the monetary authorities continue producing them.

The nation’s economic balance sheet has ballooned with rising foreign and local debts, while local companies with foreign exchange exposures struggle to survive. How is a policy that destroys corporate balance sheets considered sound economic management?

Yet, international institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and global ratings agencies continue to endorse these reforms as the best Nigeria can do, even as they widen inequality.

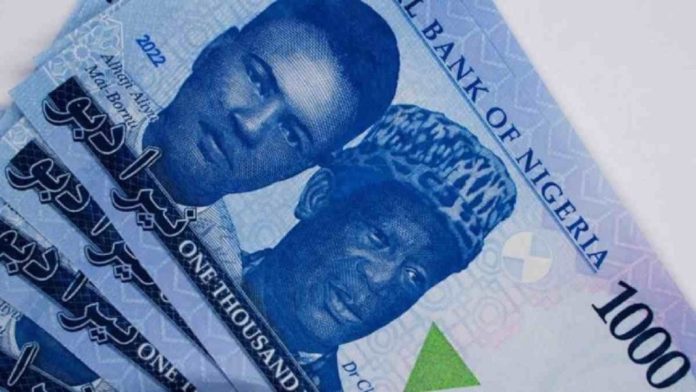

For the federal government, however, the naira’s weakness has been a windfall. Oil royalties and related earnings reportedly jumped from about N4 trillion to N12 trillion after the naira was floated, representing a 200 percent increase. This surge followed the June 2023 decision to float the naira, which saw it plunge from N473/$ to around N800/$ and close the year near N1,000/$. In 2024, it weakened further to an average of N1,600/$.

But for everyday Nigerians, this is far from good news. While government revenues swell, ordinary people see their purchasing power eroded, and businesses face mounting costs. The argument that government spending on infrastructure will eventually offset these pains often fails to resonate with millions who see no direct benefit.

Many businesses have yet to recover from the initial shock of devaluation, with some scaling back operations due to the harsh economic environment it triggered.

In reality, naira devaluation is not stopping imports; it is simply preventing poorer Nigerians from accessing dollars, while imports continue for those who can afford them. This challenges the notion that devaluation alone will fix Nigeria’s trade imbalance.

Devaluation typically supports economies with diversified exports seeking competitiveness in global markets. But Nigeria’s exports remain largely raw commodities, primarily hydrocarbons, with little value addition or diversification. When last did Nigeria export textiles or processed cocoa products at scale?

Meanwhile, when you hear figures like a N55 trillion budget, it helps to convert it to dollar terms and consider the population it is meant to serve. It becomes clear how little there is to go around—and how far the average Nigerian is from the prosperity such figures suggest.

-MarketforcesAfrica