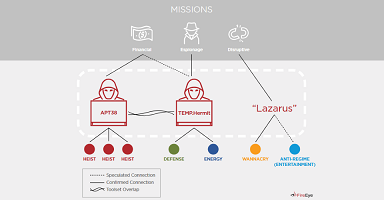

According to a new report published today by US cyber-security firm FireEye, there’s a clear and visible distinction between North Korea’s hacking units –with two groups specialized in political cyber-espionage, and a third focused only in cyber-heists at banks and financial institutions.

For the past four years, ever since the Sony hack of 2014, when the world realized North Korea was a serious player on the cyber-espionage scene, all three groups have been incessantly covered by news media under the umbrella term of Lazarus Group.

But in a report released today, FireEye’s experts believe there should be made a clear distinction between the three groups, and especially between the ones focused on cyber-espionage (TEMP.Hermit and Lazarus Group), and the one focused on financial crime (APT38).

The activities of the first two have been tracked and analyzed for a long time, and have been the subject of tens of reports from both the private security industry and government agencies, but little is known about the third.

Many of the third group’s financially-motivated hacking tools have often been included in Lazarus Group reports, where they stuck out like a sore thumb when looked at together with malware designed for cyber-espionage.

But when you isolate all these financially-motivated tools and track down the incidents where they’ve been spotted, you get a clear picture of completely separate hacking group that seems to operate on its own, on a separate agenda from most of the Lazarus Group operations.

This group, according to FireEye, doesn’t operate by a quick smash-and-grab strategy specific to day-to-day cyber-crime groups, but with the patience of a nation-state threat actor that has the time and tools to wait for the perfect time to pull off an attack.

ConnectWise: Six Steps to Managed Services Success

Incorporating managed services can help you not only stand out from other resellers, but it can also provide your business with a consistent source of monthly recurring revenue.

White Papers provided by ConnectWise

FireEye said that when it put all these tools and past incidents together, it tracked down APT38’s first signs of activity going back to 2014, about the same time that all the Lazarus Group-associated divisions started operating.

But the company doesn’t blame the Sony hack and the release of “The Interview” movie release on the group’s apparent rise. According to FireEye’s experts, it was UN economic sanctions levied against North Korea after a suite of nuclear tests carried out in 2013.

Experts believe –and FireEye isn’t the only one, with other sources reporting the same thing– that in the face of dwindling state revenues, North Korea turned to its military state hacking divisions for help in bringing in funds from external sources through unorthodox methods.

These methods relied on hacking banks, financial institutions, and cryptocurrency exchanges. Target geography didn’t matter, and no area was safe from APT38 hackers, according to FireEye, which reported smaller hacks all over the world, in countries such as Poland, Malaysia, Vietnam, and others.

FireEye’s “APT38: Un-usual Suspects” report details a timeline of past hacks and important milestones in the group’s evolution.

February 2014 – Start of first known operation by APT38

December 2015 – Attempted heist at TPBank

January 2016 – APT38 is engaged in compromises at multiple international banks concurrently

February 2016 – Heist at Bangladesh Bank (intrusion via SWIFT inter-banking system)

October 2016 – Reported beginning of APT38 watering hole attacks orchestrated on government and media sites

March 2017 – SWIFT bans all North Korean banks under UN sanctions from access

September 2017 – Several Chinese banks restrict financial activities of North Korean individuals and entities

October 2017 – Heist at Far Eastern International Bank in Taiwan (ATM cash-out scheme)

January 2018 – Attempted heist at Bancomext in Mexico

May 2018 – Heist at Banco de Chile

All in all, FireEye believes APT38 tried to steal over $1.1 billion, but made off with roughly $100 million, based on the company’s conservative estimates.

The security firms says that all the bank cyber-heists, successful or not, revealed a complex modus operandi, one that followed patterns previous seen with nation-state attackers, and not with regular cyber-criminals.

The main giveaway is their patience and willingness to wait for months, if not years, to pull off a hack, during which time they carried out extensive reconnaissance and surveillance of the compromised target or they created target-specific tools.

“APT38 operators put significant effort into understanding their environments and ensuring successful deployment of tools against targeted systems,” FireEye experts wrote in their report. “The group has demonstrated a desire to maintain access to a victim environment for as long as necessary to understand the network layout, necessary permissions, and system technologies to achieve its goals.”

“APT38 also takes steps to make sure they remain undetected while they are conducting their internal reconnaissance,” they added. “On average, we have observed APT38 remain within a victim network approximately 155 days, with the longest time within a compromised system believed to be 678 days (almost two years).”

But the group also stood out because it did what very few others financially-motivated groups did. It destroyed evidence when in danger of getting caught, or after a hack, as a diversionary tactic.

In cases where the group believed they left too much forensic data behind, they didn’t bother cleaning the logs of each computer in part but often deployed ransomware or disk-wiping malware instead.

Some argue that this was done on purpose to put investigators on the wrong trail, which is a valid argument, especially since it almost worked in some cases.

For example, APT38 deployed the Hermes ransomware on the network of Far Eastern International Bank (FEIB) in Taiwan shortly after they withdrew large sums of money from the bank’s ATMs, in an attempt to divert IT teams to data recovery efforts instead of paying attention to ATM monitoring systems.

APT38 also deployed the KillDisk disk-wiping malware on the network of Bancomext after a failed attempt of stealing over $110 million from the bank’s accounts, and also on the network of Banco de Chile after APT38 successfully stole $10 million from its systems.

Initially, these hacks were reported as IT system failures, but through the collective efforts of experts around the world [1, 2, 3] and thanks to clues in the malware’s source, experts linked these hacks to North Korea’s hacking units.

But while the FireEye report is the first step into separating North Korea’s hacking units from one another, it will be a hard thing to pull off, and the main reason is because all of North Korea’s hacking infrastructure appears to heavily overlap, with agents sometimes reusing malware and online infrastructure for all sorts of operations.

This problem was more than evident last month when the US Department of Justice indicted a North Korean hacker named Park Jin Hyok with every North Korean hack under the sun, ranging from both cyber-espionage operations (Sony Pictures hack, WannaCry, Lockheed Martin hack) to financially-motivated hacks (Bangladesh Bank heist).

But while companies like FireEye continue to pull on the string of North Korean hacking efforts in an effort to shed some light on past attacks, the Pyongyang regime doesn’t seem to be interested in reining in APT38, despite some recent positive developments in diplomatic talks.

“We believe APT38’s operations will continue in the future,” FireEye said. “In particular, the number of SWIFT heists that have been ultimately thwarted in recent years coupled with growing awareness for security around the financial messaging system could drive APT38 to employ new tactics to obtain funds especially if North Korea’s access to currency continues to deteriorate.”