Awer Mabil’s journey from life as a refugee in a hut built out of mud to scoring on his international debut is the stuff dreams are made of.

The 23-year-old grew up in a refugee camp in Kenya, where hunger and cramped conditions were everyday problems for his family.

After moving to Australia as part of a humanitarian programme, he was subjected to racism as he tried to make it as a footballer.

But he has come through it all, and scored on his debut for his adopted nation in a 4-0 win in Kuwait in October.

Mabil was born in a refugee camp in Kakuma, Kakuma after his parents fled the civil war in Sudan.

Hunger and cramped conditions were just two of the daily challenges faced by his family.

“We built a hut out of mud,” he tells the BBC’s World Football programme.”Probably the size of one bedroom in a normal house in the Western world, as you would call it.

“But you know it’s not your home. There were four of us living in it – me, my mum, my brother and sister. We got food from the UN once a month.

“Each person would get 1kg of rice, so we had 4kg in our family, and 3kg of beans. It got tricky because we had to ration it.

“We had one meal a day, which was dinner. There was no such thing as breakfast or lunch. You just had to find your way through the day and the little dinner that you had, you really had to appreciate it.”

Two-hour walk to watch football

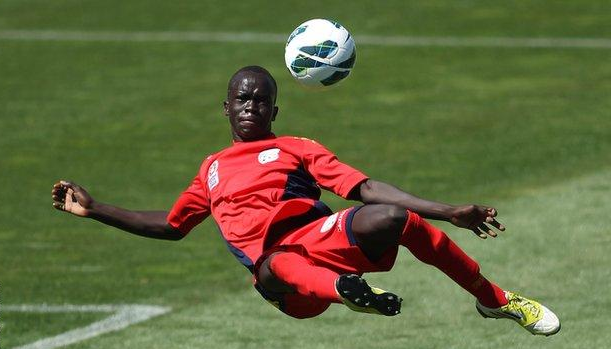

Mabil, a winger, started playing football in the refugee camp from the age of five, kicking a ball around with his friends “because there was little else to do”.

But the Manchester United-mad youngster had a long walk if he wanted to watch a football match on televison.

“I loved playing football. It was the only thing that kept me out of trouble,” he says. “I followed Manchester United a lot, but there was only one TV, two hours away, and you had to pay $1 to watch.

“If you couldn’t go, you just had to make sure that one of your friends who went told you the result.”

His life changed in 2006, when he and his family were resettled in Australia.

“I thought, ‘yeah, my chance is now – if I work hard, everything can happen and I can chase my dreams.’ That’s when it really began.

“Thanks to football, I began to speak English and express my feelings. That’s when it started to kick in.”

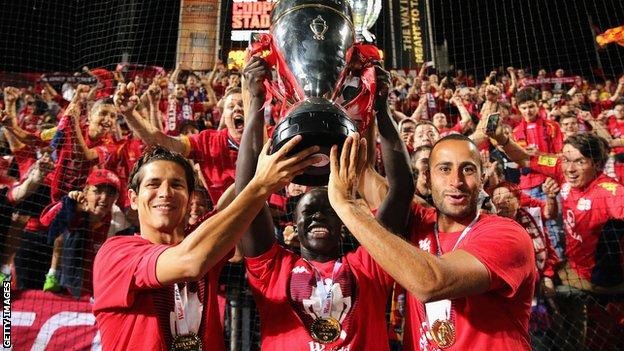

He was signed by Adelaide United at the age of 16 and had two seasons in the A-League, which included an FFA Cup win in 2014.

Racist comments ‘normal’

The changes in Mabil’s life were not all good, though. For the first time, he experienced racism – but he says he does not see Australia as a “racist place”.

“I’ve faced it a lot,” he says. “Once, when I was 16, I came home and one of my neighbours attacked me,” he says.

“The first thing I did was shut the front door and hide my siblings. I was talking to these guys while the door was shut. I said: ‘Go away.’ They kept saying: ‘Go back to your own country.’

“Apart from that, you experience day-to-day things like when you’re walking along the road there are people in cars beeping you and saying things. That’s normal.”

Despite that, he says he’s proud to represent the country.

“I represent Australia because it’s given me and my family the opportunity in life to have a second chance,” he says.

“I don’t judge Australia as a racist place. There are certain people who are racist, but it’s a country that belongs to everybody.

“It’s part of me because I’ve lived half of my life there. I call it home, so I’m proud to represent Australia.”

In 2015, he moved to FC Midtjylland in Denmark.

Three years later he is still there, and now an Australia international – his debut, on 16 October, capped by an 88th-minute goal.

“The reaction has been amazing,” says Mabil, who even received a message of congratulations from one of his idols – former Manchester United, Juventus and West Ham defender Patrice Evra.

“I grew up watching Evra playing for Manchester United,” he says. “To get feedback from these big, big guys means the hard work continues and that I’m on the right path.”

Giving something back

Mabil now has his own foundation – Barefoot to Boots – and regularly returns to Kakuma.

“I take boots, football equipment and hospital equipment and donate them to the refugees there,” he says. “If I have two weeks’ holiday, I’ll spend one week there and a week with my family.

“It was really tough [living there] but it’s something I’m really grateful for and will be grateful for for the rest of my life.

“It’s built some mentality into my head to appreciate the good times and to not give up on my dreams.”